You can strengthen your children’s reading and writing by reading aloud with them.

Okay. So that’s not ground-breaking news. You’ve heard it a thousand times, right?

Let me say, here, that I bet you could do it so much better than you’ve been doing it.

I have some teaching tips that I’d love for you to try the next time you read with your kids. You can slip in some of the following informal lessons, and they will absolutely help you to make the most of the time you spend reading with your kids.

I bet you read to your kids to get them settled into bed. (If not, you should give it a try. Reading books together makes bedtime such a special daily routine.) It’s commonly said that bedtime reading helps kids to become great readers. That can be true, but I’m not so sure that it accomplishes all that we think it does.

Here’s the thing: I know of LOTS of parents who faithfully read to their children almost every day, and too many of those children are still struggling to read on their own. Oh, they love books . . . when a parent reads TO them. But they hate reading on their own. I see it a lot. Maybe that’s what’s happening at your house.

I believe I can help.

If your kids can read grade-level texts with accuracy and comprehension, the following lessons may be just what you need to move them forward. By the way, if your kids are in elementary school, they are definitely not too old for you to read to them. It will be important, however, to read aloud books that are a bit beyond the level at which they can read and understand, independently.

(If your kids are beginning readers or they have difficulty reading the words on the pages of their books with accuracy and confidence, you’ll want to check out our Foundations for Literacy kits that are now available at bookbums.com. There you’ll find a free spelling assessment to do with your kids. When you observe what your kids understand about how words work and where their understanding breaks down, it will provide some valuable information about how to move them forward.)

Read through the following ideas and choose one or two during your next read aloud time. Remember to strive, always, to make reading together fun!

The book I used for samples in this post is The Honest Truth, by Dan Gemeinhart. This is a well-crafted book written for kids ages 8-12 (though some say it’s better for kids ages 10- 13 due to its heavy topic involving a young boy with cancer).

As I read the book, I noted some teaching points I’ll be sure to address when I have the opportunity to read it with students.

My goal for this post is not to ask you to do exactly what I’m sharing. I’m not asking you to read this book–though you certainly could. You can absolutely teach these micro-lessons with any high-quality children’s book. I simply want to share with you some ways you can e-x-p-a-n-d the reading of a great book. As your kids begin to notice what it is that authors do to make their writing great, your readers can use those same tools in their own writing.

- Expanding Vocabulary- learning new words and meanings (sometimes spellings, too)

Don’t just read over what might be confusing or unfamiliar vocabulary words. Address them. Explore their meanings together. When tutoring, I use a simple Google search on my phone, allowing the kids to type in the spelling of the identified word, to learn the definition(s). Many times, my own take on the definitions of words is not nearly as precise as it could be, so I am also teaching myself while I’m teaching kids. I like learning, and I am making every effort to inspire my kids become lovers of learning, too. Also, because Google maintains a history of your searches, it’s easy to review the words you’ve looked up. When you have a few extra minutes, pull out your phone and review the words you’ve been looking up over time. This spiraled review is extremely valuable.

So, when you notice an unfamiliar or confusing word, look up the meaning and see if that makes sense in the context of the story you’re reading. You may need to investigate another meaning for the word, so note not just the first definition, but at least the top few. Once you’ve decided which definition best fits the sentence you’ve read, commit to trying to use the word across the next few days. You can write “words I want to learn” on a list that you keep handy.

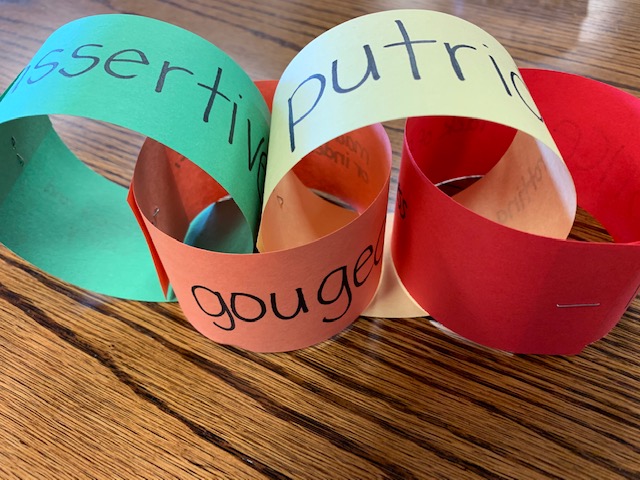

If you’re feeling ambitious, you can make a word chain with your kids. Simply cut some strips of paper (11 “ x 2”) and make a vocabulary paper chain for a cool review tool.

You may also want to compare words that have similar meanings (synonyms) and words with opposite meanings (antonyms). I love exploring semantic gradients with my students. Here’s how they work: Name a describing word such as warm. Then ask, “What word means more warm than warm?” Often, kids add words to warm like, “really, really, warm.” Try to steer them toward other words that could take the place of warm. You may do a lot of the talking at first, but with practice, your kids will get better at it. You can make a simple word collection with a stack of index cards. Begin by listing words that are warmer than warm.

warm– hot, scalding, boiling, blazing, temperate, blistering, etc.

Then, ask your kids what words could mean cooler than warm.

warm– chilly, cold, lukewarm, freezing, nippy, tepid, etc.

Make word cards for these words, too.

Finally, ask your kids to place their word cards in order from coldest to hottest. There is a lot of opinion at play, here, but if kids can justify their responses, go with it.

If you’re really ambitious, you can cut a piece of yarn or ribbon or tape and place the words, in order, along the line. You can even, as a family, decide it you agree with word placements on the gradient or if changes should be made. Again, kids should justify their opinions. This talk can be a lot of fun.

You can do the same activity with the following words:

thin

nice

good

Sometimes authors actually define their words within their writing. See the following example from the text:

crevasse- It is, basically, a giant crack in the snow and ice. A long, skinny, jagged canyon that cuts across the mountain. They can be incredibly deep. A crevasse could be only three or four feet across at the top but hundreds of deadly feet deep. Sometimes their tops get covered by snow, like the mountain’s laid a trap. If a climber falls in one, it’s almost always the end of their story. You plunge down into the darkness, down until the space gets narrower and narrower and you’re finally stuck, pinched between two ice walls, far from any rescue. You die of cold or hunger or suffocation, trapped in a dark coffin made of ice. They are a climber’s greatest fear.

Even though you don’t need to look up this word, you could still add this word to your word collection. In the classroom, I kept plenty of blank index cards on hand. I’d record interesting words and a quick definition, and then I’d post them in our classroom. When it was time to do some writing, I always challenged my students to try to include one of our featured words.

Sometimes I read ahead and had the words and the definitions ready before reading aloud. Then, I’d share the featured words, define them, and use them in a sentence. I posted them where the students could see them. As I read aloud, my students would raise a hand or give two thumbs up or wink at me when they heard the featured words within the story.

- Read it, Act it out

His mouth stayed in an o of surprise. (p. 93)

You’ll want to have some sort of signal for when to act out a word or phrase, or it could get a little crazy, but this is a great way to encourage engagement in the story, to improve understanding of what’s happening, and to introduce new words. Many times, we don’t even pause to consider that our kids have no understanding of many terms and phrases used in books. Please DO STOP (for anywhere from one to five words a day, max) to explain action word meanings and then act them out. If you hear the word again, act it out again- every time, until it’s just another word you know.

Some action words that I find myself defining often include:

ambled beamed, gaped, gasped, hoisted, lunged, lurched, murmured, scowled, trudged, pelted, etc.

I loved reading and seeing my kids gaping when I read the word gape aloud. : 0

- Italicized words- used to call attention to those words, readers’ voices “land upon” these words a little harder

Well, it would, but that was kind of the point. (p. 94)

Show your kids the words that are italicized on the page and explain why you changed your voice as you were reading. Share that the author directed you to do what you did by using those italicized letters.

- Quotation Marks “ ” – used to indicate the exact words spoken from people’s conversations

“I know what you’re doing, kid. Get off my bus. Now.”

Show your kids the quotation marks. Share the reading and let your kids say the words on the page like they’re acting in a play. You can even teach your kids to use their fingers to make quotation marks when they notice that you’re reading words that are actually spoken.

- Note that the line indents (or “dents in”) to show when there is a new speaker or a new topic or a new place.

“I’m Shelby,” she said. “I’m six.” (Note- Both of these sentences are spoken by the same person, so they’re both on the same line, even though it’s two sentences with unspoken words between them.)

“Okay.” (Note- new line = new speaker)

“What’s your name? (Note- new line = new speaker)

I almost said it, then remembered. My brain scrambled and spat out the first name that came to mind. (Note- No quotation marks are used here, because the line is not spoken aloud. It’s indented because it’s a new person’s thoughts.)

“Uh. Jess. Jesse, I mean.” (Note- It’s the same person, but now it’s spoken words, so we have a new line.)

Notice that you could read the words within quotation marks (darkened, above) like it’s a play with different lines for different characters. If I own the book I’m reading, I like to have my students highlight what is in quotation marks (on a couple of pages where dialogue is heavily used). I enjoy reading it like a play so my kids get a better grasp of why authors do what they do as they are writing. Their decisions all work together to make it easier for readers to understand the story the author is sharing.

- Dash – used to indicate a break in the sentence

“Oh, Jess, that’s a silly thing to say, that’s just—“

But I interrupted her.

(p. 99)

Tell your kids when you see one of these dashes. Make note of how that dash impacted how you read the text. When you get to a dash in your read aloud, draw a dash in the air to show how and when it’s used.

- Ellipsis /ih-lip-sis/ . . . used to show that some words were left out or that there is a pause. I teach my kids to think . . . “There’s . More . Coming .”

I . . . I know it’s hard, baby, but there’s no use in being afraid. (p. 99)

When I read aloud to kids, I often use my pointer finger to make three dots in the air. The kids would copy me and say, “There’s… More… Coming… ELLIPSIS!”

- Metaphor- a word or phrase used to compare one thing to another thing, suggesting a likeness

I looked at the narrow black ribbon of the highway stretching out between the tall, dark pine trees. (p. 111)

The raindrops were sharp, angry nails hammered into my jacket. (p. 139)

My legs were wet spaghetti.

After I had shared the definition and lots of examples with my classes, when my students heard a metaphor (I often paused to signal that something special was happening in the text…), they’d shout out, “Metaphor!”

- Repetition- the same word or line used multiple times

. . . and I felt tiny and terrified and alone, alone, alone. (p. 163)

It had books and maps and movies and key chains. And snacks. (p. 163)

It all hung on her, she knew. On the secret she held, the secret no one knew she was holding. It was a heavy secret. (p. 103)

That’s the truth. (p. 3, p. 27, p. 59, p. 110, p. 129, p. 147, p. 148, p. 161, p. 177, p. 215)

Note- That’s the truth was repeated, again and again, throughout the book

10) Lists- a compilation of items or actions that, together, convey a message that helps to tell the broader story

More of nothing but the rain and the tires and the engine and the radio and the sound of us three breathing there together. (p. 150)

I could still hear the country music, softly, could still feel the truck’s warmth, still smell the hot air and coffee and sandwich and cigar smoke. (p. 162)

Authors often use lists. When you find a list in the books you read, note it. Then, with some practice, your kids will recognize them on their own. When beginning to experiment with using writers’ crafting tools within their own writing, using lists is a great place for your kids to begin.

11) Varied Sentence Structure – an inserted/integrated genre- an unexpected type of writing found within that text that is not typically associated with the text being read

Authors often integrate different kinds of writing within their work.

Dark day spent alone.

Pacing, crying, thinking hard.

Somewhere a lost friend.

*Haiku is a form of poetry that is used throughout this book. Many books other kinds of writing such as text messages, letters, poems, email messages, etc.

Note, aloud, when you see a letter, or a text, or a poem, or any other form of writing within the pages that you’re reading with your kids. Invite your kids to look at it/acknowledge it, and share that they, too, can use this technique in their own writing.

12) Extra spaces between lines- means time has passed &/or the location has changed

We’ll walk until . . . we die?

The bridge came closer, step by step, through the darkness. (p. 112)

Beginning writers can get bogged down in telling all of the details in a story. You can share that authors often “skip to the good/important parts” when they tell stories. They simply show they’ve moved on to another time or place by leaving an empty line on the page.

13) Simile- comparing things using the words like or as

The round little white pills dropped like hard, heavy snowflakes. (p. 94)

I closed my eyes and held the memory in my mind like a smooth river stone. (p. 97)

My students got really good at noticing when authors used similes. Yours will, too.

14) Personification- giving human characteristics to things that are not human

Rain was all around me, poking at the puddles in the gravel. (Can rain really poke?)

*Note, too, the alliteration, poking at the puddles.

The aloneness howled louder than the wind. (Can aloneness howl?)

15) Rhyming Words- words that have the same (or even just nearly the same) ending sounds from the final vowel sound to the ends of the words

I managed to pinch one between my thumb and a numb finger. (p. 126)

You’ll have to notice this first, and then bring it to your kids’ attention. This one is a little tricky to notice when kids are captivated by a story.

16) Onomatopoeia- a word that, when spoken aloud imitates the sound the thing that is named

My teeth clattered against each other, letting my breaths out in a shaky hiss. (p. 125)

You notice it first, and your kids will soon be able to identify it. They have a lot of fun just saying the word onomatopoeia. And, no, it’s not too big of a word. Kids love knowing sophisticated words!

17) Alliteration- neighboring words that begin with the same sounds

My feet hit the bottom, bumping boulders and scraping rocks . . . (p. 123)

In the morning I was stiff and sore and starving . . . (p. 129)

When you draw attention to it, your kids can’t help but enjoy identifying alliteration. Remember to have your kids identify it by name- alliteration.

18) Descriptive Words- words that enable to reader to see the scene in his or her mind’s eye

A wide, fallen log reached over the foaming water, leading from the bank where I was standing to the sandy island. (p. 113)

Ask your kids, “Could you draw this scene? If so, then you’re visualizing it. The author’s words enable you to see the scene in your mind’s eye.” You can also have your kids draw when you read to the scenes.

19) Lovely Lines- well-crafted lines that just sound and feel magical when vocalized

Road stones crunched under the soles of my shoes. (p. 111)

20) Fun Facts- tidbits of factual information embedded within a story

The cotton balls were coated with Vaseline— I’d read that they were the best fire starters that you could make. (p. 125)

Make note with your kids when an author gives a cool factoid. Who knows? It may come in handy someday. (And yes, I tried it. It works.)

21) True-to-Life Voices- authors use self-created words to convey the personalities of their characters (intentional solecism)

Everybody outa have a dog . . . A life ain’t much of a life without a dog in it. S’what I always said.

20) Chapter Changes- when authors make a shift in the story

A chapter change can indicate a switch from one character’s point of view to another character’s point of view.

The whole numbered chapters, in this book are from Mark’s point of view. (1, 2, 3, …)

The half-numbered chapters are from Jessie’s point of view. (1½, 2½, 3½, …)

In this text, the author also used a different font to distinguish the points of view.

22) Circular Stories- when the end of the story points right back to the beginning of the story

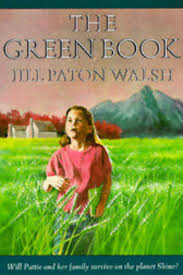

Another circular story that I highly recommend is The Green Book, by Jill Paton Walsh. It’s science fiction, and it’s fantastic!

And my students always LOVED it!

I hope you have lots of fun extending the reading of great books with your kids! You won’t believe the advantage your kids will have in school when they have command of these tools. When they can recognize authors’ crafting tools in the books you read to them, they can recognize them in the books they read on their own— AND they can begin using them in their own writing.

If you think this is too sophisticated for your child, remember that I taught all of these to my second graders! They were seven years old. Trust me. It’s not too early. My students LOVED the stretch. Yours will, too.

@dangemeinhart